A research project undertaken by Mikva Challenge DC’s Elections in Action Youth Leadership Team

Written by Amir Rashed BS and Rebecca Allen BS of The George Washington University School of Medicine , Robyn Lingo , Executive Director of Mikva Challenge DC , and Katherine Douglass MD MPH , of The George Washington University School of Medicine.

The Gun Violence Epidemic has become an all too familiar tragedy for members of our most vulnerable communities here in the District of Colombia. The last three years in the District have seen an uptrend in homicides and shootings; 2018 saw a 38% rise in homicides from 2017, including the tragic loss of 13 minors1,2. To date, 2019 has already seen a 16% increase from the previous year, suggesting a dangerous trend in increase of violence in the district1. Perhaps most troubling is that these shootings occur regularly in the vicinity of public schools. During the 2016-2017 school year, 177 shots were recorded within 1,000 feet of 86 schools across the District3. Young people are falling into the crosshairs of gun violence in the District and are increasingly cognizant of the effect gun violence has on their communities. Even with clouds of anxiety over safety and security, these same youth are actively brainstorming solutions to their community’s violence problem. Through the Mikva Challenge, an organization founded aiming to expose and integrate youth into civil society, high school aged DC natives have undertaken the challenge of measuring the attitudes, thoughts, and perceptions of their peers on issues of safety, gun violence, policing, and programs offered by DC government to promote neighborhood welfare.

Students participating in the Mikva Challenge designed a survey to determine how violence impacted their peers, how their peers view law enforcement officials, and knowledge of resources offered by DC government to reduce violence. Over 115 students at over 20 different schools participated. In addition to raw data, narrative information was also collected during this survey allowing for a more nuanced look behind the hard numbers. In conjunction with students from the George Washington School of Medicine and Health Sciences, the collected data was analyzed for possible trends related to Ward residency and ethnicity.

“I feel mostly safe, but do not walk alone when it’s very dark/late. This is because I have heard gunshots very close to my house…”

The data revealed interesting findings. Respondents living in Wards 7 and 8 report feeling just as safe in their Ward as students living elsewhere (60%, 77% respectively vs 84.3% overall average reporting feeling safe in their neighborhood). While these percentages are close in value, the sample size of this study was correspondingly small possibly obscuring true significance. The narrative data, however, paints a more complex picture. One student who responded feeling safe in their neighborhood said, “I feel relatively safe, because I live in a relatively peaceful, family-based community, however, every once in a while, there is an occasional crime that shocks the neighborhood, like a murder or shooting”. Another respondent who replied yes to feeling safe in their neighborhood reported, “I feel mostly safe, but do not walk alone when it’s very dark/late. This is because I have heard gunshots very close to my house…”. Students described their neighborhoods as “safe” environments despite objectively unsafe circumstances. Even more disturbing is those students who responded “No” to feeling safe in their neighborhood, adding comments such as, “I live in between two hoods and often hear gun shots while I’m home”.

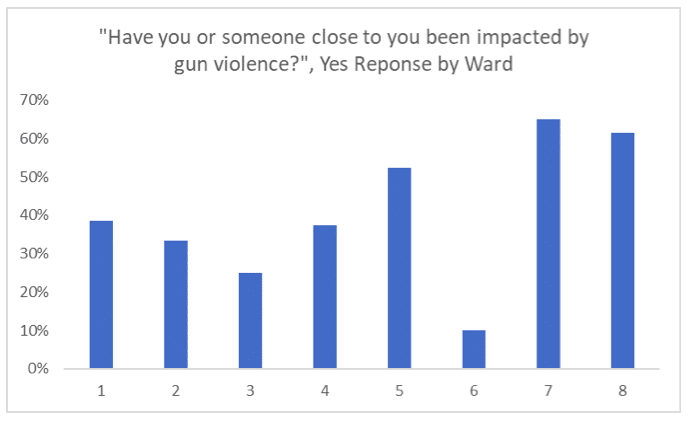

Figure 1: Percent impact by gun violence by Ward. Highest positive response reported in Ward 7 with 65% “Yes” rate.

Gun violence was shown to affect a sizable number of the students polled. Over 50% of African American students questioned answered yes to “Have you or someone close to you been impacted by gun violence?” compared to all other ethnic groups (<35%). A majority of students living in Ward 7 or 8 responded positively to this question (>60%). The narrative data has multiple mentions of specific students who were killed by gun violence. Other students mentioned family members or family friends who were victims of gun violence, for example: “My uncle was shot at close range, then stabbed and beat at a bus stop at night”.

Students were additionally queried regarding their perceptions of policing and law enforcement, showing a division of opinion. 54% of the student population respondents replied that the amount of policing is adequate to address crime in their neighborhood. When these results were analyzed by race, the African American cohort showed a near perfect 51% to 49% yes-to-no split of opinion. 80% of White students replied in the positive. When asked if afraid to approach the police, the numbers also reflected a near perfect split. The narrative data, however, reveals deeper issues. One student who responded “No” to being afraid to approach the police explained, “A few of my neighbors are police officers, and I have always been taught that police are there to help and keep you safe. I’m white so I’m not likely to get profiled by police”. Another respondent who replied “No” stated, “The only times I have been afraid of approaching the police are when I’m hyper sensitive of the racial tension in my neighborhood. I am white and have lived in my neighborhood since I was 3 and in recent years gentrification has caused a lot of tension and sometimes makes me afraid of going to the police”. An African American student who responded “Yes” stated, “The police in my neighborhood tend to be very hostile, especially in the warmer months when they increased police presence…. they treat residents like hostiles and criminals”. These narrative responses describe deeper issues adding to the complexity of the gun violence issue here in the District.

Image 1: Mikva Challenge Students hard at work brainstorming solutions to violence

An additional goal of this survey was to gauge knowledge with regards to action taken by DC government to tackle the epidemic of gun violence. Student knowledge of DC government efforts are poor; more than 70% of the students polled had never heard of any DC government specific programs placed to promote nonviolence. Of the 29% who responded “Yes” to hearing of one of the listed programs, the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement was the most known entity with over 60% mentioning the ONSE. Overall, this reflects a gap between DC government public outreach efforts and public perception of local government efforts.

There are numerous preexisting community-lead initiatives and organizations working to stem the tide of gun violence here in the District. Groups such as Building Community Resilience, the TraRon Center, the Pathways program, and Cure the Streets (both through the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement) work in tandem with the goal of abating gun violence in the district. The Mikva Challenge represents an especially powerful conduit for change as it empowers young across the city to engage and tackle issues that directly impact their lives. The youth of DC may be the demographic most impacted by gun violence; simply walking to school is too often unsafe for the children and minors who call DC home. The cost of gun violence in terms of friends and family lost and trauma sustained growing in this environment makes it become clear that this demographic stands to gain the most, and thus, is the most invested in seeing an elimination in gun violence. Working with The Mikva Challenge, these youth can channel their intention and vigor to change the world around them.

A Road Map to Safer Streets

The ultimate goal of this work was to aid in building a safer city for everyone, including these bright minded youth. The data demonstrate a bridgeable gap between DC government and its citizen stakeholders. Important results were discovered, even among the relatively small number of participants. Based on the data collected, the following items represent discrete actionable steps to moving towards this goal:

- Increase and sustain police outreach to community groups to foster more trusting relationships

- Targeted efforts to showcase DC resources (Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement’s Violence Intervention and Prevention, Pathways Program) in order to increase awareness of organizations working to end violence, possibly in form of Ad Campaign or Program showcases at community events.

- Implementation of an expanded survey collected from a larger number of DC teenagers

- Data from the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/district-crime-data-glance

- King, C. I. (2019, August 23). Gun violence in D.C. is treated as a normal part of life. That needs to change. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/gun-violence-in-dc-is-treated-as-a-normal-part-of-life-that-needs-to-change/2019/08/23/ac30d87c-c4f5-11e9-b72f-b31dfaa77212_story.html

- Gunshots And Lockdowns: When Nearby Gun Violence Interrupts The School Day. Alana Wise-Luis Melgar – https://gunsandamerica.org/story/19/06/17/gunshots-and-lockdowns-when-nearby-gun-violence-interrupts-the-school-day/